By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

Blog

Car Trouble

When Jerome Powell described last year’s inflation surge as largely transitory in nature, we all had the hopes that that would mean that pandemic-related supply and demand shocks would be self-correcting (which they probably will be, to an extent), and that they would be over soon. But if you google the word transitory, you find that the Oxford Language definition of transitory is simply two words: “not permanent”. Eventually isn’t the timeframe we were seeking, but it may be the reality we face—in other words, we may be through with the pandemic, but the pandemic still isn’t through with us.

Auto production, for instance, still hasn’t returned to normal, and this week Toyota announced that it wouldn’t be able to meet its production goals for February due to the continued semiconductor chip shortage.

Toyota’s original goal was 850,000 units, but the company now is anticipating production of only 700,000 units. Toyota is also suspending production at 8 plants in Japan, for between 2 and 13 days.

Besides chip shortages, port problems and labor shortages on the US West Coast are also contributing to the industry’s supply chain woes. Moreover, as you might guess, the current Omicron wave hasn’t helped matters, especially in conjunction with China’s zero-COVID policy—in the midst of mass testing and restricted movement, Toyota has suspended production in the Chinese city of Tianjin. It’s hardly surprising that production shortages combined with strong demand have resulted in higher car prices, with inflation spilling over most acutely into the used car market.

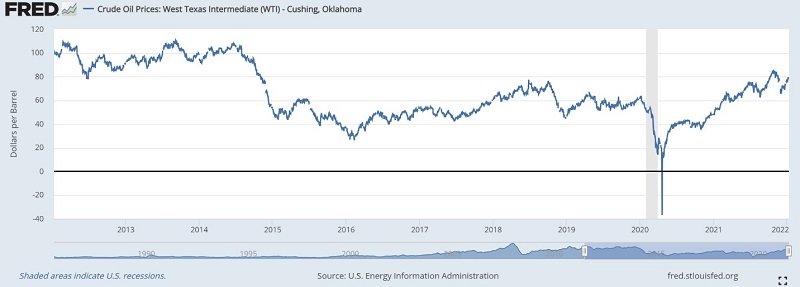

Even if auto production normalizes by 2023, some industries may not return to pre-COVID norms of operations. Higher oil prices have followed from an increased demand for oil, but OPEC producers, which cut supply in 2020, are having difficulties ramping up production. As Stanley Reed notes, there are numerous causes for limited oil output.

The years prior to COVID were not kind to oil producers; given this backdrop, it is not surprising that US and global producers are reluctant to invest in higher capacity. Regulatory and investor concerns stemming from climate change policy, as well as increased competition from renewable energy, may also be leading to investment hesitancy. In the interim, many OPEC producers are falling short of production quotas.

Political turmoil in Nigeria, aging oil fields in Kuwait, and lack of investment in Venezuela has left Saudi Arabia as the country best positioned to increased output—but Saudi Arabia has been reluctant to do so. Considering that the country benefits from below-quota production in other OPEC countries and ensuing high prices in the oil market, Saudi Arabia may be content with the status quo.

The one constant in life is change, and while some of the COVID-induced changes may be reversed, others may persist. It’s easy to imagine increased chip production and alleviated supply chain bottlenecks restoring auto production to higher levels in the next 12-24 months. But oil production is a complex, long-term, multifaceted challenge, and the supply shifts caused by COVID in 2020 may limit future oil availability for years to come.

###

JMS Capital Group Wealth Services LLC

417 Thorn Street, Suite 300 | Sewickley, PA | 15143 | 412‐415‐1177 | jmscapitalgroup.com

An SEC‐registered investment advisor.

This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument or investment strategy. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to be or interpreted as a recommendation. Any forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes only and are not to be relied upon as advice.

‹ Back

Comments